India’s presidency has done something unprecedented: it has brought the Global South into the spotlight—where the world’s majority live, the challenges they face, and the opportunities they offer for a sustainable and prosperous world.

In a world marked by the rivalries of great powers and the urgent need for collaborative action, the G20 has become a stage where realpolitik unfolds in real time. And yet, this forum—which accounts for 85 per cent of global GDP, 75 per cent of trade and an overwhelming majority of climate-warming pollutants—offers hope for cooperative action to shape the global future. India’s G20 presidency, with its mix of geopolitical challenges and transformative potential, marks an important moment in the forum’s history.

India has received this presidency during a particularly tumultuous period in world politics. The ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine has strained relations between the West and Russia to levels not seen since the Cold War, if not worse. Likewise, Sino-US relations are historically low, and Sino-Indian ties have hit a nadir. These conflicts, coupled with the lingering economic effects of Covid-19 and the increasing frequency of climate disasters, have started to hurt global economies.

Given this backdrop, the absence of a consensus document from recent ministerial meetings under India’s G-20 is not unexpected. There are doubts about whether the current summit in Delhi can yield a joint communiqué, given the substantial divide between Russia, China, and developed countries. However, the current divide does not overshadow India’s achievements during its presidency. India’s term at the helm of the G-20 will be remembered for its agenda of challenging the status quo and reimagining global cooperation.

India’s presidency has done something unprecedented: it has brought the Global South into the spotlight—where the world’s majority live, the challenges they face, and the opportunities they offer for a sustainable and prosperous world. By advocating for the African Union’s inclusion in the G-20, India is reshaping the conversation, ensuring that the voices of the Global South are not just heard but amplified. Beyond dialogue, the call for channelling more funds to these regions for climate action and sustainable development goals marks a significant shift in priorities. India has provided these nations with a space at the proverbial table, one that the future G-20 can’t ignore.

Demanding Financial Fairness

Often referred to as the ‘Finance G-20,’ India’s presidency has explicitly called for a fundamental reform to establish a fairer global financial system that benefits all. The stark reality of the current international financial arrangement is that poor African countries pay four times more interest on loans than the US and up to eight times more than wealthy European countries. India’s concrete proposals on debt crisis management, multilateral development bank reforms, and international financial architecture have accelerated a long-overdue conversation on creating a more equitable financial future.

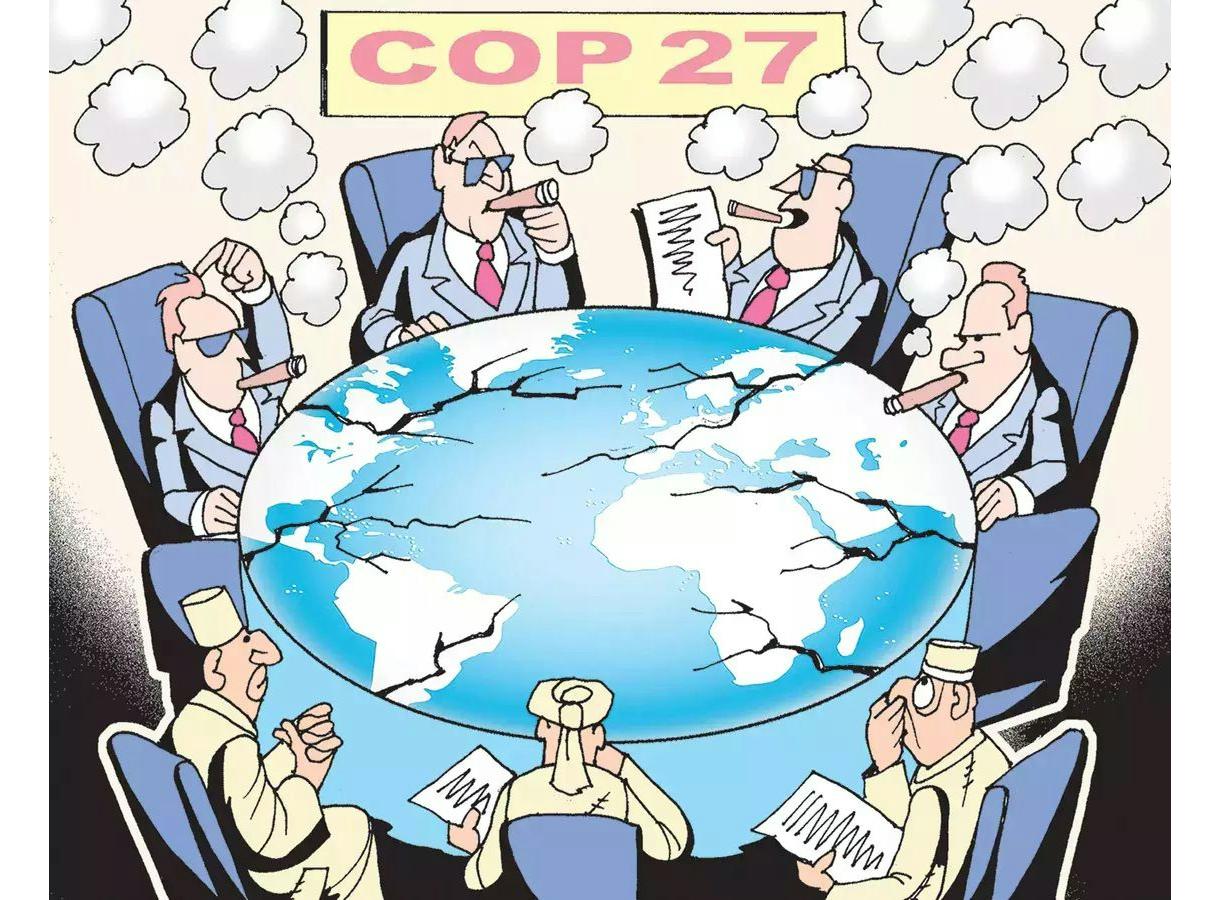

Climate Action & Accountability

Under India’s guidance, climate action has gained renewed momentum. Emphasising lifestyle impacts on climate, India has underscored the importance of individual responsibility and people-centred solutions. This is especially important considering that the wealthiest 1% of the world’s population is responsible for twice as much carbon dioxide emissions as the poorer 50% of the world. Through initiatives like Mission LiFE, India has challenged the developed world’s consumption and pollution habits, pressing for a democratisation of climate action.

Besides, India’s G-20 will also be remembered for its inclusivity within and outside the country. In line with its presidency theme—’Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam,’ or ‘One Earth, One Family, One Future’—India has conducted over 220 meetings in 60 cities in all 28 states and 8 union territories, involving voices from all corners of the globe and within India itself. It has also showcased India in a new light as a diverse and dynamic nation eager to bridge divides and foster collaboration.

One important thing to remember is that in international diplomacy, progress is at a canter rather than a gallop, built around continuity. So a presidency alone is not sufficient to push an agenda. India, therefore, will have to work with other countries to get its transformative agenda implemented over time. Fortunately, India’s presidency is the second in a line of four consecutive presidencies allotted to emerging economies—an occurrence not slated to happen for another two decades. India therefore, has a great opportunity to work closely with Brazil and South Africa, the next two presidencies, to advance the agendas of the Global South.

India’s G-20 presidency will be remembered not just for its momentary milestones but for its audacity to envision and shape a more equitable and sustainable global future. Under India’s guidance, the roadmap appears promising, with pathways to financial equity, digital inclusivity, and environmental sustainability shining brightly. And while the ink may still be wet on its term, the true implications of India’s presidency will unfold in the years to come.