This article appeared in The Times of India

Baku conference has shown up the glaring inadequacy of the international climate framework and the deep mistrust among nations. Bad news for the fight against climate change

Mahatma Gandhi’s famous critique of the Cripps Mission in 1942—describing its proposal as “a post-dated cheque on a crashing bank”—perfectly captures the essence of the climate finance deal adopted at COP29, the recent UN climate conference in Baku, Azerbaijan. However, there is one crucial difference: while Cripp’s figurative cheque was decisively rejected, the Baku finance deal, despite criticism from several nations, including India, was adopted. This highlights the broader failures of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and global efforts to address the climate crisis.

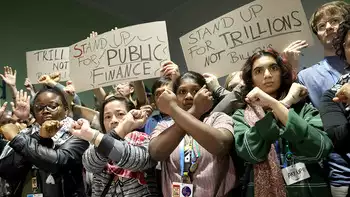

The Baku conference began with developing countries demanding $1.3 trillion in annual funding from developed nations by 2030 to tackle the climate emergency. Their proposal called for at least $500 billion in public funding, with the remainder provided as concessional private finance.

Yet, after two weeks of contentious negotiations, developed countries committed to only $300 billion annually by 2035, with no binding pledge for public funding. Instead, the deal vaguely promises to source funds from “a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources.”

Worse still, the agreement permits developed countries to include climate-related loans from multilateral development banks, such as the World Bank, as part of the funding pool. This means developed nations are under no obligation to increase funding beyond the current $100 billion annually until 2035. Moreover, they retain the freedom to count virtually any climate-related financial flow to developing countries as part of their contributions.

The political future of this deal is equally uncertain, as there is little chance that the incoming Trump administration will honour the commitments made by the Biden administration.

In essence, the Baku deal offers little more than a continuation of the status quo, allowing developed nations to sidestep meaningful financial obligations while leaving developing countries to shoulder the escalating costs of the climate crisis.

However, this is not surprising. In 2009, developed countries pledged $100 billion annually in climate finance by 2020. They met this target in 2022, and even then, nearly 70% of the funds were provided as loans at market rates, burdening developing nations with debt. Expecting trillions from nations that struggled to deliver billions was always unrealistic. So, how should developing countries secure meaningful climate finance?

The path forward requires fundamental reforms in the global financial system to empower developing countries to deal with the climate crisis and revamping the UNFCCC to enable effective international collaboration.

The current global financial system is stacked against vulnerable nations. Poor African countries, for instance, pay interest rates on loans that are four times higher than those paid by the U.S. and up to eight times higher than those paid by wealthy European countries. This disparity is being exacerbated by the climate crisis.

A report by the UN Environment Programme, Climate Change and the Cost of Capital in Developing Countries, found that climate vulnerability has already increased the average cost of debt in 25 vulnerable developing countries by 117 basis points. This translates to an additional $40 billion in interest payments over 10 years on government debt in these countries alone. This means developing nations are currently paying hundreds of billions of dollars to wealthy countries and their banks due to climate risks. The report predicts that this financial burden will double over the next decade. In effect, the current financial system is profiting from their climate vulnerability.

To address this injustice, several proposals, including those advanced during India’s G20 presidency, have been on the agenda for years. These include measures like debt crisis management, multilateral development bank reforms, risk mitigation programmes, and blended finance strategies. Implementing these reforms would enable developing countries to invest more in mitigation and adaptation using their own resources.

Reforms within the UNFCCC are equally urgent. At Baku, India accused the COP Presidency and the UNFCCC Secretariat of manipulating the process to secure the adoption of the finance deal, reflecting a deep trust deficit in the institution. Additionally, the growing influence of the fossil fuel industry in UNFCCC proceedings threatens its credibility and relevance.

The reality is that under the Paris Agreement, all countries are now on their own to mitigate, adapt and pay for the costs of climate impacts. The UNFCCC is now simply a platform to collect, synthesize and disseminate information. It doesn’t have the tools to drive global collective action to combat climate change. So, persisting with UNFCCC in the present form is counterproductive.

There are many ideas on the table including making UNFCCC a smaller solution-driven forum where countries report their progress and are held accountable to their pledges. Other suggestions include establishing multiple sectoral and regional platforms, such as on energy, transportation, agriculture, industry etc., rather than relying on a single global framework.

The Baku conference has laid bare the glaring weaknesses of the international climate framework and the deep mistrust among nations. It is now up to Brazil, the host of COP30, to restore trust and drive meaningful progress. Without decisive reforms, the global fight against climate change risks being mired in inadequacy and inaction, with all the attendant hazards for life on earth.

Chandra Bhushan is one of India’s foremost public policy experts and the founder-CEO of International Forum for Environment, Sustainability & Technology (iFOREST).