COP28 will really test rich nations’ commitment to climate finance. Big Oil & Big Gas will be under severe scrutiny.

There is always a hype build around the annual United Nations Climate Change Conference. Every Conference of the Parties (COP) is projected as a do-or-die meeting. Success is typically measured by the grandeur of new pledges, with the n=host country basking in the glow of any significant commitments. However, the 28th COP, which begins on November 30 in Dubai, is unique because it is not so much about new promises (though there will undoubtedly be some) but what happened to the old ones. The question to be answered in Dubai this December is; have the countries kept their promise, and if not, what’s next? Dubai COP, therefore, is the first “official” reality check of the climate crisis. It is also a reality check for the oil and gas industry and for the commitment of the rich world to support poor countries in dealing with climate disasters.

The Paris Climate Accord, adopted in 2015 and signed by 195 countries is a unique treaty. While it has set an international goal to keep temperature increases within 1.5-2°C, it cannot force countries to cut emissions. Countries pledge voluntary commitments to reduce emissions, called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), but these are not legally binding, and there is no penalty for non-compliance. What the Paris Agreement has is a process to review pledges every five years, called Global Stocktake (GST), to check where the world stands on climate action. The assumption is that disclosing information will put moral pressure on countries to enhance their commitments. The Dubai COP, therefore, is crucial because the results from the first-ever GST will be discussed here.

While all assessments clearly show that the current emissions trajectory will lead to a 3°C warning by the end of the century, the big question is what kind of message from GST will be delivered in Dubai. Would it be greenwashing, or would it call out countries for vapid and unmet commitments? This is important because the outcome of GST will inform the next round of NDCs that countries need to declare by 2025. These commitments will be implemented through 2025 and thus would decide climate action for the next 10 years. So, the right messaging from COP28 is crucial to unequivocally indicate what countries, developed and developing, are required to do to put the world on track to meet the Paris Agreements goals in the next decade, a decade which will decide whether we will win or lose the climate battle.

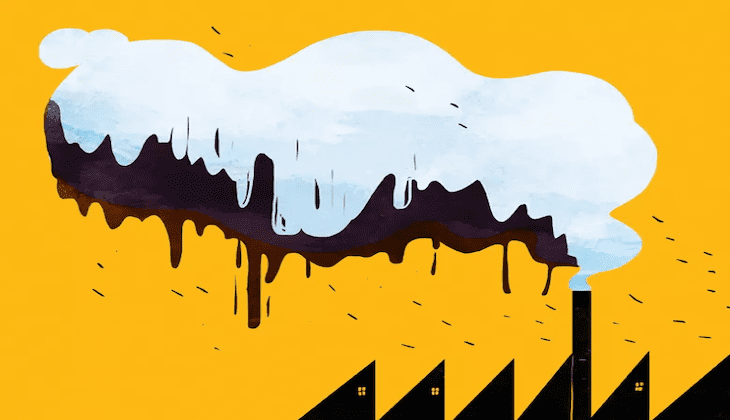

Then there’s the elephant in the room. Often touted as a cleaner fuel than coal, oil and natural gas (O&G) in 2022 accounted for 54% of global greenhouse gas emissions; coal accounted for 40%. O&G is the developed world’s fuel of choice. In the EU, for instance, they contribute about 60% of the total energy; coal’s contribution is 10%. The reliance on O&G is even greater at 70% in the US. In contrast, the dependence on coal is higher in emerging economies like India, China, South Africa and Indonesia.

Two years ago, at COP26 in Glasgow, an agreement was reached to phase down coal use. This concession was wrung from countries like India that depend heavily on coal to meet their energy demand. Despite repeated attempts, no such commitments have been made for O&G, although it is abundantly clear that prolonged reliance upon such fuels is entirely incompatible with the 1.5°C goal. Dubai, however, is the perfect venue to make such a commitment.

The UAE is the world’s eighth largest petroleum producer and very mush a petrostates. A recent Guardian expose found that the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) has the most investment in new petroleum production projects. The CEO of ADNOC is Sultan Al Jabar, the man that the UAE has selected to preside over COP28. So, the stage is set for what the executive director of the International Energy Agency has called a “moment of truth for the (global) oil and gas industry’s efforts on climate”. Would the developed world and the petrostates agree to the O&G phase-down, or would this be another lost opportunity?

Perhaps the most critical issue for developing countries at COP28 is action on the Loss and Demage Fund (LDF), whose creation was agreed to last year at COP27 in Egypt. Recent years have seen a rapid acceleration of climate-related disasters. These impacts are being borne disproportionately by smaller, poorer, and inevitably less developed countries, which are least responsible for the climate crisis. LDF was envisioned to channel funds from rich economies into those most vulnerable to climate disasters.

While the agreement to create the LDF last year was undoubtedly momentous, we will see whether this vehicles will be given any teeth in Dubai. If it is left toothless and penniless, the Global South should accept that the North has no intention of taking any responsibility for its historic emissions and has no serious plans to help those in need.

The commitments made in Dubai on LDF and action on O&G will determine whether the goals of UNFCCC can be met. Will developing countries be made to bear alone the costs of adaption to a rapidly warming planet while the rich burn petrol and utter empty platitudes? Or will the developed world finally take responsibility for its historical emissions?

In essence, COP28 isn’t just another gathering; it’s a milestone event where the international community must confront the harsh truths about our collective (and differentiated) efforts to combat climate emergency