This article originally appeared in Vol LVI No. 29 of the Economic & Political Weekly, published on 17 July 2021.

The article discusses why it is an imperative for India to begin deliberation on a just transition from coal in light of some of the compelling factors. It then evaluates what a just transition in India might entail building on an onground study of a coal district in Jharkhand, one of India’s top coal mining states. And fi nally, it outlines the planning and policy considerations that will be necessary to support a

just transition.

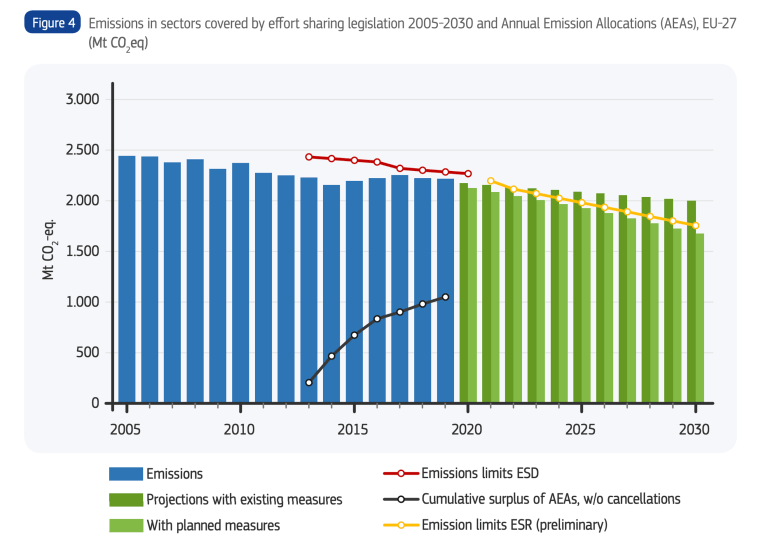

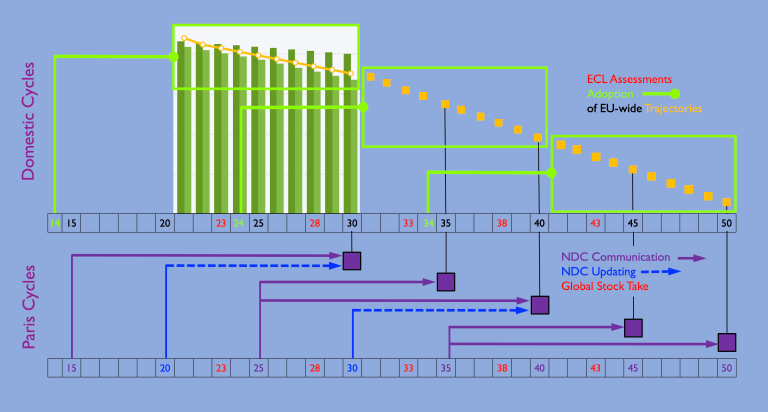

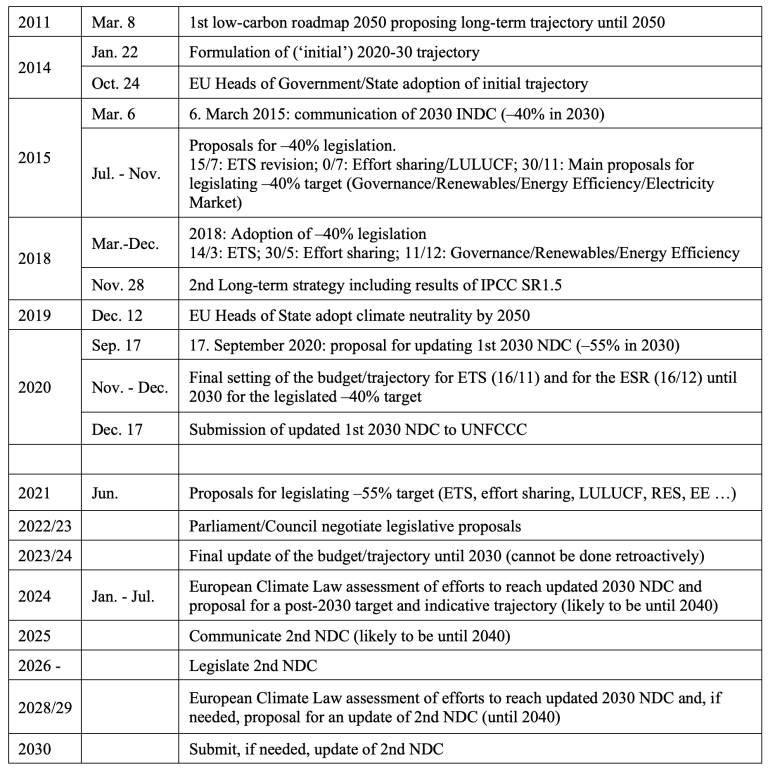

Over the past two decades, a growing body of research on climate change has made it clear that a shift away from the fossil fuel economy is inevitable. This will entail a system transition in electricity generation, based on renewable energy sources and simultaneous phasing out of coal-based power by 2050 (IPCC 2018).

However, there are socio-economic consequences of such a transition that cannot be overlooked. A fundamental concern is about the fate of fossil fuel industry workers and local communities who are dependent on it. Just transition as a policy and planning concept tries to address this. Originally advocated by labour unions (Galgóczi 2018), and later merging with the broader debate on environmental justice, the concept underscores the need of ensuring social justice in the shift towards a low carbon, or a carbon neutral future (Morena et al 2019).

The basic idea of a just transition is to secure a sustainable and decent livelihood for the people who are dependent on the fossil fuel industry through proper planning and investments. Simultaneously, there must be efforts to eradicate poverty in those regions, and to build thriving and resilient communities (ITUC 2017). It insists on the idea that a healthy economy and a clean environment can and should coexist (Just Transition Alliance 2018).

The socio-economic aspect of the energy transition is now an essential component of the climate change discourse. In 2015, just transition was included in the preamble of the historic Paris Agreement (2015) as, taking into account the imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities.

Since then, it has become an important policy component of climate change mitigation action. Countries of the global North are coming up with just transition policies and plans. In most countries of the global South, including India, the discussion on a just transition is either in its infancy or has not been initiated (Pai et al 2020).

India and Just Transition

In India, a policy discourse on a just transition has not been initiated yet because of our high dependence on coal for energy security and industrial growth. However, it is time for such a discussion to begin considering five compelling factors.

First, in India, coal is losing its edge progressively. While overall coal mining is still profi table, with the country’s largest coal producer Coal India Limited (CIL) recording profi ts, about two-thirds of the CIL-operated coal mines are unprofi table and are closing down (Bhushan et al 2020). These are primarily low yielding underground mines, which are a disproportionately high number compared to their cumulative production capacity. As per the latest information of the company, of the 352 mines CIL and its subsidiaries currently operate nearly 45% are underground mines (158 mines). However, they account for only about 5% of the company’s raw coal production (CIL 2020). The employee liability of these mines is very signifi cant, as they employ about 40%–45% of CIL’s total workforce. As per internal inputs, the loss from continuing with these mines is about 16,000 crore per year, about the same as the company’s annual profi t in 2018–19. The alarming issue is that these unprofi table mines are closing down in an unplanned manner (Bhushan et al 2020). Besides underground mines, old opencast mines are also proving to be unprofi table and are either closed or temporarily discontinued. For example, in Jharkhand, one of India’s top coal producing states, more than 50% of the coal mines are currently closed, including both opencast and underground mines (Department of Mines and Geology 2020).

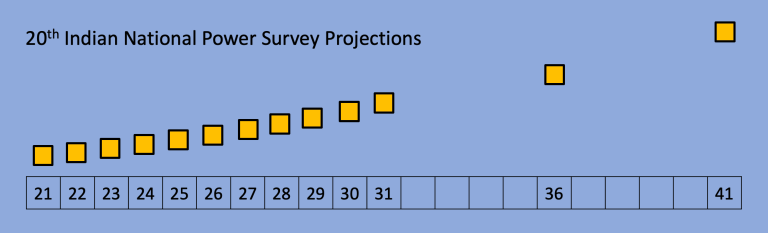

Second, coal is facing a major challenge due to the growing cost competitiveness and reliability of power from renewable energy sources. The installed cost and tariffs of utility-scale solar photovoltaic plants in India have fallen by 85% since 2010 (Henbest 2020). In 2019, it stayed around 2.50–3.00/kWh, depending on the location of the offtake risk (Saran et al 2019). This is 20% to 30% cheaper than the cost of power from existing coal plants. Solar power prices are expected to fall further in the coming years to around 2.00/kWh by 2030, while the cheapest pithead coal power price is likely to rise to `4.85/kWh by that time (CPI and TERI 2019).

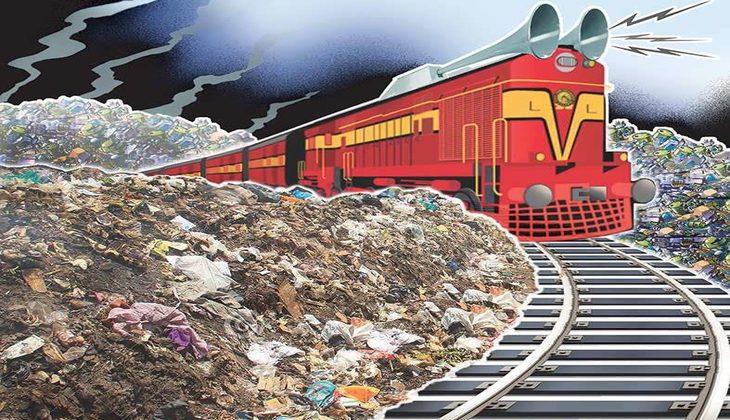

The third reason is the pollution and environmental burden of coal-based power and coal mining. Coal-based power plants are the largest source of industrial pollution in India. Of the entire industrial sector, they alone account for 60% of suspended particulate matter (SPM) emissions, 50% of sulphur dioxide (SO2), 30% of nitrogen oxides (NOx), and 80% of mercury (Hg) emissions (Bhushan et al 2015). Considering this, the environmental standards of coal-based power have been made progressively stringent. In 2015, the Ministry of Forest, Environment and Climate Change (MoEFCC) imposed new standards on coal power plants to limit their emissions of SO2, NOx, PM and Hg. The estimated capital expenditure required to meet these standards is about 86,135 crore. This will add between 0.32/kWh and `0.72/kWh to the existing power tariffs (or around 9% to 21% to their average generation tariff) depending on the size of the units and other factors (Garg et al 2019). For coal mining, MoEFCC in 2010 had identifi ed most of the top coal mining areas as critically polluted areas. These include Hazaribagh and Dhanbad in Jharkhand, Singrauli in Madhya Pradesh, Korba in Chhattisgarh, and Angul (Talcher coal-fields) in Odisha, among others (Bhushan and Banerjee 2015). In addition, coal mining remains one of the major factors for forest-land diversion. On an average, an estimate of the last 40 years shows that 20%–25% of total forest land diversion is due to mining, and about half of that is for coal (Bhushan etal 2020).

Fourth, we need to plan a transition away from coal to reverse the legacy problem of resource curse in the coal regions. Most of India’s top coal mining districts suffer from this, with the local people facing displacement and deprivation due to resource extraction. In many of India’s top coal mining districts there is a high proportion of deprivation and poverty. For example, in districts such as Singrauli, Sidhi, Chatra, Godda, Surguja, Korba, and Sonbhadra, about 40% or more of the people are multidimensionally poor, exhibiting very poor status of health, education, and living standards (as per Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative multidimensional poverty index calculator). This is nearly twice the all-India average of 27.9% (Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative 2020).

Finally, is the urgency of climate change action. For India, this becomes necessary not only considering our environmental obligations, but also given the economic and social costs of the climate crisis. India is the fi fth most vulnerable country to climate change impacts, as per the Global Climate Change Risk Index 2020 (Eckstein 2019). Under business-as-usual scenario, climate change will increase the stress on the country’s natural ecosystems, agricultural output, and freshwater resources, while also causing escalating damage to infrastructure. These will have severe consequences for the country’s food, water and energy security, public health, and for sustaining the country’s economic growth (Bhushan et al 2020). In 2018, India’s economic losses due to climate change were the second-highest in the world, with the estimated loss at 2.7 lakh crore, which is equivalent to about 0.36% of its gross domestic product (GDP) (Eckstein 2019). The Ministry of Finance (2020), has further estimated that the cumulative costs of climate change adaptation till 2030 will be 85.6 lakh crore, equivalent to nearly 58% of India’s GDP in 2019–20 at constant prices (National Statistical Offi ce 2020).

Global experiences of successful coal transitions show that if a transition is planned in a timely and deliberative manner, it will not be a tradeoff between

the environment and economy, and can lead to positive social and environmental outcomes (Bhushan et al 2020). In fact, just transition will be an appropriate policy move for the Government of India (GOI) to complement its vision of energy transition and to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Evaluating a Just Transition

In countries of the global North, the experience on just transition has been primarily related to the formal workforce of the coal industry and associated socio-economic factors (Bhushan et al 2020). However, in India, the situation is different considering that most of our key economic sectors are based on an informal economy (Labour Bureau 2014). Global experiences also suggest that there is no one standardised approach for a just transition. The dependence on fossil fuel, and the nature of the transition will vary from country to country and from region to region within a country. Any approach to a just transition thus needs to be evaluated in a country-specific manner and planned in the context of respective fossil fuel/coal mining regions (Bhushan et al 2020).

Ramgarh district of Jharkhand constitutes a representative case to evaluate what just transition means for India. One of Jharkhand’s top coal mining districts, Ramgarh produces about 13 million tonnes of coal per year. However, production has been steadily declining over the past four years. Currently 50% of the total of 24 coal mines in the district are closed or have been temporarily discontinued due to various reasons, including unprofitability. 1 The remaining mines have a productive life of 10–25 years, and there are very few new ones in the pipeline ( Department of Mines and Geology 2020). Therefore, coal mining activities in the district will largely be phased out in the next decade or two. While coal still remains central to the district’s economy, Ramgarh is as an appropriate case to understand what a coal phase-out will look like, and what it will entail.

Study Approach

The Ramgarh study is based on a mixed approach of primary and secondary research. A primary survey was conducted of 406 households in the district, that were selected through a process of strati fi ed random sampling.2 Samples were chosen from three geographic strata: 0–3 kilometre (km), 3–10 km, and beyond 10 km, from the mine/mine cluster, to minimise the possibility of clustering and selection bias.3 Besides, 14 focus group discussions were conducted with various stakeholder groups in the three main coal mining blocks, namely Mandu, Patratu and Chitarpur, covering 138 participants. Personal interviews were also conducted with state government representatives, the district administration, public representatives, panchayati raj members, labour unions, coal industry officials, and civil society groups.

Secondary data was obtained for understanding the coal industry profi le in Jharkhand and Ramgarh, and for analysing the demographic distribution, economic status, social infrastructure, and key development parameters in Ramgarh. The data also helped to evaluate the political economy of coal mining in the region, and to identify the various stakeholder groups that will be affected, and are related to the just transition process.

Key Observations

The Ramgarh case study brings out four key observations that are important for understanding just transition in India.

First, the dependence on coal mining for income is signifi cantly high. Out of the total surveyed households, 27% (equivalent to 54,000 households in the district) depended directly on coal for an income. Nearly three-fourths of them (71%) were part of the informal coal economy, including coal gatherers and sellers, casual labourers, and other contractual workers (including businesses). Only 29% had formal employment with coal companies.

Majority of the people belonging to the informal economy also fall within the low-income group, with a monthly household income between 5,000 and 10,000. This group of people also lack labour protection or social safety.

Second, income dependence on coal is spatially concentrated. While more than 40% of the households within a radius of 3 km from the mines derived direct income from coal, this proportion sharply declined to less than 17% for households living beyond 3 km of a mine. In fact, beyond 10 km from coal mining areas, agriculture was observed to be the most signifi cant source of employment. The district’s overall worker distribution, as per government data, also indicated high agricultural dependence, particularly in the rural areas, which is as high as 75% of the total main workers.

Third, the distributional impact of coal mining in the region has been extremely limited, benefi ting only a few. The district remains extremely poor in terms of social infrastructure or access to basic amenities. For example, there is nearly a 50% defi cit in the required number of primary healthcare centres. Moreover, even the existing ones do not meet the necessary Indian public health standards in terms of medical staff, treatment facilities, etc. The same situation is with access to education. Only 16% of the schools offer secondary/higher secondary education, with average enrolment below 50%. With respect to people’s access to basic amenities, such as clean drinking water, only about 17% of households in rural areas have access to the piped water supply. These are the areas which are also affected by mining. In fact, Ramgarh falls in the list of aspirational districts of the NITI Aayog, given its poor human development indicators (NITI Aayog 2018).

Besides social infrastructure, coal mining has also not improved the overall economic status of the district. Ramgarh’s per capita GDP is nearly half of the all-India average. This places the district among the low-income category as per global standards. Over 63% of the district’s households have a monthly income below `10,000 (Bhushan et al 2020).

Finally, and most importantly, a focus on coal mining and related industry over decades has stymied the development of other sectors and the diversifi cation of the economy. Coal remains the single largest contributor to the district’s GDP, with a share of about 21%. In addition, other industries are also coal-reliant, such as coal washeries, thermal power plants, sponge iron units, refractories, etc. On the contrary, other potential sectors such as agriculture, forestry, fi sheries, and service sectors remain grossly underdeveloped. The situation has also contributed to a perceived sense of coal dependence in the mining areas. This is evident from the fact that while 27% households reported a direct income from coal, nearly three-fourths of the surveyed households expressed a sense of “perceived” dependence.

All of the above-mentioned factors, such as high proportion of informal workforce, low-income, poor social infrastructure and development indicators, a coal-centric economy, and underdevelopment of other economic sectors puts the district at a high risk from an unplanned coal mine closure. It therefore becomes imperative to plan a transition that is timely, deliberative and just.

Developing Policy Mechanisms

Just transition planning in India will not be a linear question of substituting a “mono” industry (coal) along with its workforce. Considering the nature of dependence and the poor socio-economic status of most coal mining areas in India, just transition will require “structural changes” to support a broad-based socio-economic transition. An integrated approach will be required to reverse the “resource curse” in coal mining areas, create sustainable economic opportunities, and build climate resilience. The Ramgarh experience also clearly brings out that, considering the socio-economic complexity of the coal regions and the varied stakeholders, planning for a just transition must be a phased and deliberative process.

There will be six key components of just transition planning at the district level. This includes, defi ning a time frame for a just transition (including of phased closure of coal mines and coal-based power), establishing an inclusive transition planning mechanism, providing alternative employment opportunities for formal and informal workers in the short term, planning economic diver-sifi cation (including industrial restructuring) for the long term, improving social and physical infrastructure to build community resilience, and securing fi nancial resources to support a just transition.

However, a just transition plan cannot be implemented at the district level in absence of a well-structured governance mechanism, which is based on utmost principles of cooperative federalism between the union and the state governments, and an inclusive decision-making process by engaging various stakeholders.

The governance framework of just transition must include eight key pillars. These include strong support of the union and state government(s) on developing policies and mobilising financial support, a diverse coalition among various actors and stakeholders, an effective communication strategy on just transition to build stakeholder confi dence, economic diver-sifi cation and social sec urity planning, coal sector transition planning, development of social and physical infrastructure development, and securing public and private investments for the transition.

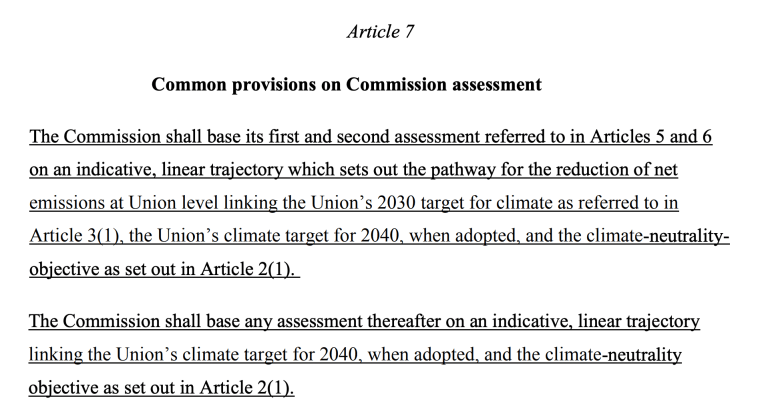

On the policy front, a crucial aspect will be developing a “national just transition policy.” The union government should develop the policy, including components of coal phase-out strategy at the national- and state-levels, plan for phasing out coal-based power and simultaneous incentivisation of clean energy, and regulatory revisions of the coal industry pertaining to mine closure and reclamation, leasing/lease transfer, la-bour, etc. The union government’s support will also be crucial for building on existing laws and schemes to enable locally deliverable actions, providing a financial package, and pushing for an international framework at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to support just transition in developing countries.

The state government, on the other hand, will be at the front line for dealing with just transition. This will require building a broad-based consensus, and a strategic action plan to phase out coal mining and coal-based power, develop-ing economic and industrial strategy to steer away from coal dependence in terms of revenue, employment, and industries, and develop a state-level policy on just transition aligned with the national framework.

The actual planning and implementation will happen at the district level, where all stakeholders will need to engage through a participatory process.

Conclusions

The overall scenario of coal mining and coal-based power in India, and specifi -cally the Ramgarh experience, shows that just transition is not a consideration of the future anymore. The issue is here and now. The Ramgarh study is a telling case of the subnational status of coal mining and coal regions. In many coal districts, mines are being temporarily or permanently closed without any framework in place to support the local economy and restore the local environment. Therefore, there is an immediate need to develop just transition plans and a policy framework for these areas to avoid economic and social disruptions. A well-planned just transition is also necessary to compliment India’s ambitious plan for energy transition, and enhance its efforts of climate change mitigation action.