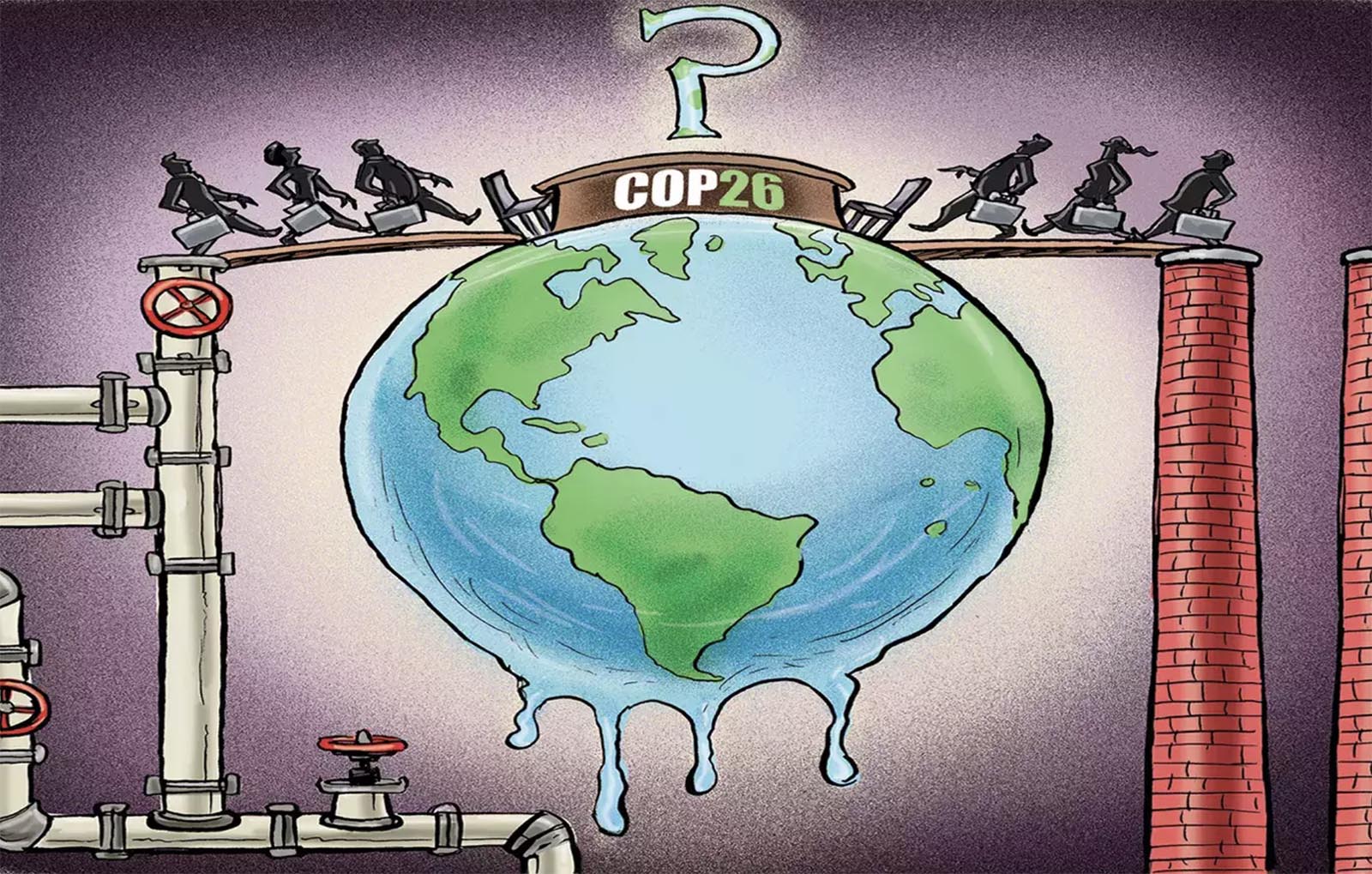

Glasgow will not solve the climate crisis but it can fast-track global climate collaboration.

A great hype has been created around the 26th Conference of Parties (COP26) at Glasgow. John Kerry, the US climate czar, has called this meeting the world’s “last best chance” to avoid climate hara-kiri. Similar sentiment has been expressed by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. More than 100 world leaders will attend this climate gala, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Joe Biden.

This is not the first time such hype has been created around climate summits. I can list at least three (two of which I attended) – Kyoto in 1997, Copenhagen in 2009 and Paris in 2015 – where the noise was deafening, but the outcome was muted. Unfortunately, Glasgow COP is heading in the same direction.

Over the last few months, a long list of demands has been put forth by various governments. The UK is pushing for a treaty to “consign coal power to history”, the US wants a net-zero deal, the Association of Small Island States (AOSIS) has demanded a 1.5°C declaration. Least Developing Countries (LDCs) want climate polluters to pay them billions of dollars for loss and damage, and Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDCs) want $100 billion climate finance and carbon space. Unfortunately, most of these demands will not be met because the groundwork has not been done to achieve them.

Take the case of coal power phase-out. The UK is pushing to end coal power by 2030 in developed countries and by 2040 in the rest of the world. But it has failed to get support from most coal-consuming countries, especially the top two consumers, India and China.

The reason is simple: Unlike developed countries that depend on gas for electricity, coal provides 70% of India’s and 62% of China’s electricity production. While phasing out of coal power is essential to combat the climate crisis, so is gas power. Countries are not convinced that prioritising one over the other is the right way to move ahead. Also, there has not been any discussion on how this coal transition will happen and who will pay for the closure of coal mines and power plants.

As a sizeable population depends on coal for livelihood in countries like India, huge investments are required to transition coal regions to non-coal economies. But, there has not been any discussion on global cooperation on coal transition. So, without discussing the nut-bolts, expecting a coal power treaty is unrealistic.

Likewise, there are disagreements on loss and damage. Developing countries are now facing a new reality – the destruction unleashed by the climate crisis is taking lives, destroying assets and infrastructure, and costing vast amounts of money in relief and reconstruction. They are demanding that the big polluters compensate them for the losses. But the developed countries have refused to negotiate any responsibility for climate-induced losses. This issue is going to be a significant sticking point at Glasgow and may derail the negotiations.

Similar disagreements exist on all major proposals. So, what should we realistically expect from Glasgow?

COP26 is taking place in the background of a vast trust deficit that emerged between countries during the Trump regime; the vaccine apartheid and the unilateral withdrawal of the US from Afghanistan have further eroded the credibility of developed countries. Hence, the pretence of the developed countries that everything is hunky-dory is misplaced. Therefore, their attempt to forge an alliance on issues like net zero is destined to become high-sounding declarations that are ritually announced at all COPs.

But the Glasgow meeting can achieve some important outcomes, the most important being the rule book for the Paris Agreement. Over the last six years, countries have struggled to finish the rule book and operationalise the Agreement in its entirety, mainly due to disagreements over the design of the carbon market. Theoretically, the carbon market can enhance mitigation, reduce cost and transfer real resources to developing countries for decarbonisation. At Glasgow, negotiators must set robust rules to eliminate past loopholes and ensure the carbon market works for the planet.

Glasgow is also an opportunity to kick-start the process of confidence-building to bring back the global collaboration on track. Both developed and developing countries must cross the aisles, understand each other’s concerns, and announce confidence-building measures.

Developed countries can put out a new plan for climate finance that is ambitious and credible. A recent report on climate finance road map shows how little money is being given by them. For example, in 2019, developed countries provided $16.7 billion as a grant. This means that every person in developed countries contributed just $1 per month for climate finance. Developed countries can surely afford more than this. A credible climate finance plan from them is, therefore, crucial.

Similarly, developing countries need to discuss their decarbonisation plans because there is no carbon space to emit. Even if developed countries reach net zero by 2030 (which is unlikely), developing countries will still have to start reducing emissions very soon. So, a serious plan on decarbonisation from developing countries would go a long way in building confidence in the process.

#TelltheTruth is a popular hashtag for COP26. It exemplifies the frustration of young climate campaigners with the negotiation process. At COP26, leaders must tell the truth. Dishonesty and falsehood are the reason why the three decades of climate negotiations have achieved little.

The writer is CEO, International Forum for Environment, Sustainability and Technology (iFOREST)