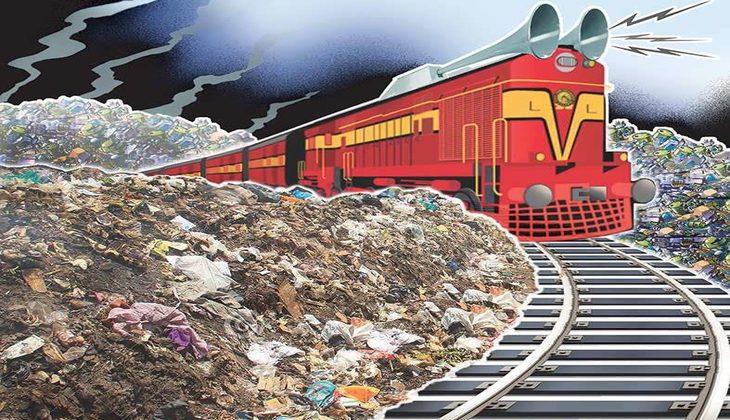

Humanity’s path to becoming the dominant species on earth has been in large part due to our ability to generate and control large amounts of energy beyond what our bodies can produce. The vast majority of this external energy that is used outside of our bodies – historically and even today – has been released through the act of combustion, specifically the burning of biomass, both fossilised as in the case of things like petroleum and coal as well as simply dehydrated as in the case of firewood, dung and so on. It is only in the last 150 years or so that we learnt to control a more efficient and flexible form of energy: electricity. However, even this electricity has been mostly generated through the process of combustion. In the age of man-made global warming, it is important to remember that each act of combustion releases air pollutants like particulate matter that harm our health and carbon or carbon equivalent emissions that contribute to the planet’s heating.

Currently, India’s ‘energy’ sector (cooking fuel, electricity, heat and transport) accounts for 75.6 per cent of carbon and carbon equivalent emissions.[1] These are the by-products of the combustion economy that currently powers our lives and economy. Importantly, this energy is largely imported, putting a question mark on India’s energy security. In 2024-25, 88.3 per cent of crude oil, [2]46.6 per cent of natural gas and 25.8 per cent of coal was imported.[3] All this while, India’s per capita energy use is 1/10th of countries such as America and less than 1/4th of global average.

Clearly, we need to produce more energy domestically and do so more cleanly than we have managed thus far. If we intend to meet our commitment to being carbon neutral by 2070 and energy independent by 2047, while keeping our economy growing and citizens’ lives improving, we must transition from a combustion economy to an electron economy. We have here the chance to make huge gains by enhancing energy security, reducing pollution and health costs, improving the availability of and access to energy in general and electricity in particular, and mitigating the climate crisis.

The electron economy

In a combustion economy such as what we currently operate in, we use multiple sources and channels to meet our energy needs. We use electricity grids to light and condition our homes, gas pipelines or gas cylinders (or burn biomass) to cook food, gasoline pumps to power our vehicles and a combination of energy sources run our factories. In this economy, electricity plays a relatively minor role. For instance, currently only 21.6 per cent of all the energy consumed in India is in the form of electricity, the remaining 78.4 per cent is direct use of coal, oil, gas and biomass in our factories, vehicles and homes.[4]

In an electron economy, electricity is the prime mover and a majority of energy used is in the form of electricity – lighting, heating and cooling homes, cooking, transport and industry will all be powered by electricity rather than burning fossil fuels. The goal for such an economy is that eventually all electricity is generated directly by renewable sources rather than the much more inefficient combustion of fossil fuel that generates steam, which turns turbines and then produces electricity. This is the only way to reach net zero goal by the middle of the century. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), to stay within the critical 1.5 degree Celsius (C) climactic threshold, 70-85 per cent of the world’s electricity must be supplied by renewables by the year 2050. Can India, which meets only 21.6 per cent of its energy requirement through electricity, and 78.4 per cent of this electricity is generated by burning fossil fuels, move to an electron economy by 2050?[5] In other words, how realistic is it for India, where non-fossil sources like renewables, hydropower and nuclear only provide 30.7 per cent of the energy supply, to meet a large majority of its energy needs through non-fossil electricity?[6]

Falling prices

In the past years (2014-15 to 2024-25), renewable power has grown at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.0 per cent and has reached 50.0 per cent of the total installed capacity of the power sector.[7] The installed capacity of the non-fossil fuel sources, including renewables, hydro and nuclear, is now 51.6 per cent of the total.[8] There are reasons to believe that this trend would continue, and renewables will become the dominant source of energy in India.

The biggest challenge is that renewable sources of energy cannot be turned on and off the way a coal power plant can be in response to changes in demand. They are produced when conditions are favourable – sunlight and wind are strong and cannot be produced when, for instance, the dam reservoir is empty. Thus, the wholesale adoption of renewables is only viable if adequate energy storage systems are available to store the excess energy during production peaks and disburse it during periods when demand is higher than production. Fortunately for us the cost of renewables has been dropping rapidly in India over the last few years to the point where installing capacity for solar energy is already 35.5 per cent cheaper than that of coal, historically the cheapest source of electricity.[9] The cost of Indian solar power is now more competitive than in any other nation of the Asia-Pacific; we must capitalise on this advantage. In addition, the cost of battery storage has fallen by 8 per cent year on year. Battery storage cost is projected to drop by 46.7 per cent in the next decade. The results of these cost reductions are already visible. The cost of round-the-clock (RTC) renewable energy has fallen to near US$50 per megawatt hour (MWh). The result: RTC is already competitive with new coal power plant in India.

The final piece of this puzzle is, green hydrogen, produced with renewable electricity, which can be used for combustion as well as the transfer of electricity with no by-products but water. Its availability is crucial in order to decarbonise the hard-to-abate industries and heavy transport sector. The biggest impediment to its production till now was the high cost of renewable electricity. With falling renewable prices and government incentive programmes, green hydrogen is now becoming a reality. In 2023, the government allocated Rs.19,744 crore to the National Green Hydrogen Mission, targeting 5 Million Metric Tonnes (MMT) of annual capacity of green hydrogen by 2030. [10]

Infrastructure needs

While renewable-plus-storage is increasingly looking more economical than a coal-fired grid, the true benefits of a modern decarbonised electricity system lie in changing the nature of the grid. Renewables-plus-storage is more responsive to peaks in electricity demand than fossil fuel plants. However even where we have this system, the cost savings from this precision and responsiveness are not being fully rewarded by the current grid. To realise these benefits, we need smart grid solutions that allow real-time management of generation and transmission in response to demand.

India’s interest in such solutions has so far been motivated by the need to reduce energy theft and transmission losses. As a result, India has largely prioritised demand-side smart metering, with limited investment in power supply coordination. Investing in an overhaul of the grid not only lays ground for decarbonisation, it makes economic sense in the present. As part of its stimulus package after the 2008 financial crash, the US government invested US$ 3 billion in smart grids. The investment returned US$ 6.8 billion in economic benefits, including 50,000 new jobs and US$ 1 billion in additional government revenue. This is one of the highest ‘multiplier’ effects seen for any kind of government infrastructure investment.

In addition, the transformative potential of renewable-plus-storage is highest in areas, which are currently under-served by the electricity grid. While India has linked nearly all villages to the grid, the cost of grid electricity in many remote areas is often prohibitive. Solar-plus-storage mini-grids have potential to provide cheaper electricity in these remote areas than grid power. This is partly because renewables offer greater variation in scale, allowing them to be adapted to smaller markets. They can also be sited closer to communities, reducing transmission and access costs.

Investing in renewable-plus-storage mini-grids for these under-served communities will bring significant socio-economic returns. It will also drive innovation in the sector more broadly, further reducing the cost of modern power even in over-supplied electricity markets. Finally, it will reduce the emissions generated by burning biomass in these regions, and contribute significantly to the health of women in particular who suffer from inhaling cooking smoke.

Just transition for the coal sector

The more pressing challenge ahead is the phasing down of coal as there are communities and jobs dependent on it. This is why we need an ambitious ‘Just Transition’ policy, which directs investment and support systems into communities transitioning away from coal employment. Since these are often the communities who have been marginalised in India’s development story, just transition is not only a climate policy, but a long overdue economic course correction. If we combine a just transition policy with a clear phasedown schedule, India can be a healthier clean electricity economy by the middle of this century.

In summary, India needs to modernise toward an electron-based economy, and away from burning fuels for light and heat. The technological headwinds in favour of renewable electricity are unmistakable. We need to seize the opportunity to be at the cutting-edge of the coming transformation.

[2] Snapshot of India and Oil Gas data, December 2025

[3]Energy Statistics of India, 2025

[4]Energy Statistics of India 2025

[5]Energy Statistics of India, 2025

[6] ICED Dashboard, Niti Aayog

[9] Coal-to-Solar Generation Swaps for India

[10] National Green Hydrogen Mission