Railways fascinate me. Professionally, I advocate for a massive expansion of rail networks to address the air pollution and climate crisis. Rail transport is not only highly energy efficient compared to road and air transport, it can also completely shift to renewable energy. It will, therefore, play a significant role in reducing emissions from the transport sector. The Indian Railways has recognised this potential and has set a target to achieve net zero carbon emission by 2030, the most ambitious climate target set in the country.

Personally, I love long train journeys. Travelling on the Coromandel Express from Howrah to Chennai, Netravati Express from Mangalore to Mumbai (when it ran on metre gauge), and the Rajdhani from Delhi to Mumbai and Kolkata are some of my favourite travel memories. But during all these times, like most people, I took for granted the noise, the open toilets (now stinking bio-toilets), and the waste along the tracks and stations. But as Indian Railways is expanding, modernising and privatising, environmental issues we overlooked in the past mustn’t be ignored anymore.

Indian Railways is big in every aspect; it runs the fourth largest railway system globally and carries 8 billion passengers and more than a billion tonnes of freight a year. These numbers are projected to increase by 50% over the next 10 years. As it’s already one of the largest consumers of water and energy and generator of waste, its environmental footprint will increase significantly in a business as usual scenario. While Indian Railways has made significant progress in energy efficiency, renewable energy and cleanliness, there are grave concerns of water and noise pollution and waste management.

Let’s first start with the law. For a long time, Railways had taken the view that the country’s key environmental laws – the Water, the Air, and the Hazardous Waste Act – do not apply to its operations. Therefore, no railway station took permits from the pollution control boards (PCBs) or complied with the regulations. A recent National Green Tribunal judgment has categorically rejected this stand and has directed the Railways to abide by the laws. However, the Railways is still reluctant to comply, and most stations are still operating without consent from PCBs.

The situation’s no different with railway sidings/ goods sheds, a major source of air pollution. The majority of these sidings are operated by private companies, but many are working without consent. Reports by the Comptroller and Auditor General and the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) have confirmed poor air pollution management at these establishments.

Poor handling of wastewater has also been identified as a significant concern by the CPCB. Since most stations have not installed Effluent Treatment Plants (ETPs), effluents generated from cleaning trains and stations are discharged into municipal drainages or low lying areas. The situation is the same with Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs).

Every day about 5,000-6,000 tonnes of fecal matter is generated from toilets in the trains and on stations. This is equivalent to the fecal waste generated in a large metro city. While 95% of trains have installed bio-toilets, they are “no better than septic tanks” and the water discharged no better than raw sewage. In the absence of STPs at most stations, the sewage is discharged untreated. In a country where hotels with more than 20 rooms are being directed to install STPs, Railways’ failure to install ETPs and STPs is discriminatory, so say the least.

Noise pollution is an even more problematic issue. More noise is considered useful in the railway establishment for accident prevention. There are strict instructions to honk at all gates, turns and at the time of entry and exit from a station. During the night, train drivers are instructed to honk to ensure they’re alert and not sleeping. Though accidents are a real problem because of encroachments and unfenced railway tracks, continuing with the current strategy is counterproductive because of enormous health implications.

High noise levels lead to poor learning, aggression, hypertension and cardiovascular disease. For millions of citizens living near railway stations and tracks, the railways’ current position is an untenable proposition. Indian Railways will have to find a solution that balances imperatives of accident prevention and noise control.

On waste management, Indian Railways has made some progress. It runs ‘Swachh Rail Abhiyan’ for improving cleanliness and waste management. While there’s no doubt that cleanliness has improved significantly, and some of our railway stations match global standards, the same cannot be said about solid waste.

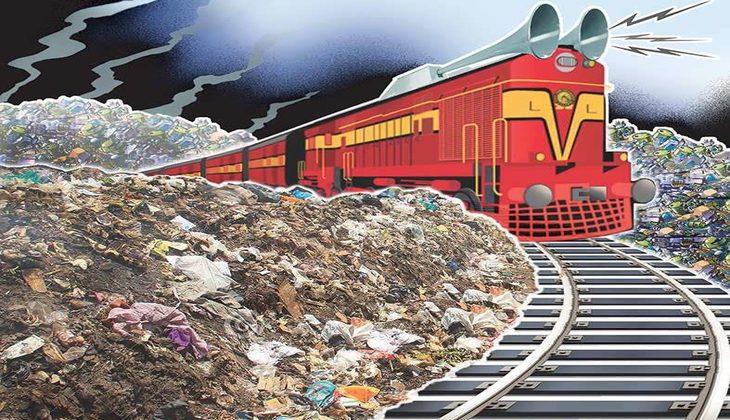

Indian Railways seems to have an ‘out of sight, out of mind’ approach while dealing with solid wastes. Wastes are collected mainly in unsegregated form and disposed of along with the municipal wastes or burnt or dumped near the track. In fact, the Railways has not even enforced the single use plastic rules of various states, including the national ban on polythene bags. Overall, while Indian Railways is doing a lot on energy issues (because it also makes good economic sense), the same cannot be said about pollution or waste.

The fundamental problem seems to be a sense of ‘exceptionalism’. Railways have historically operated independently of the civil administration. It doesn’t follow many of the laws applicable to a similar service industry like the airline industry. It’s time these anomalies are corrected. Indian Railways should comply with environmental laws and work with civil authorities to solve pollution and waste issues. Its low energy footprint must be matched with sound environmental management.