Only 7% students enrolled in dedicated green courses; nearly half unaware such courses exist

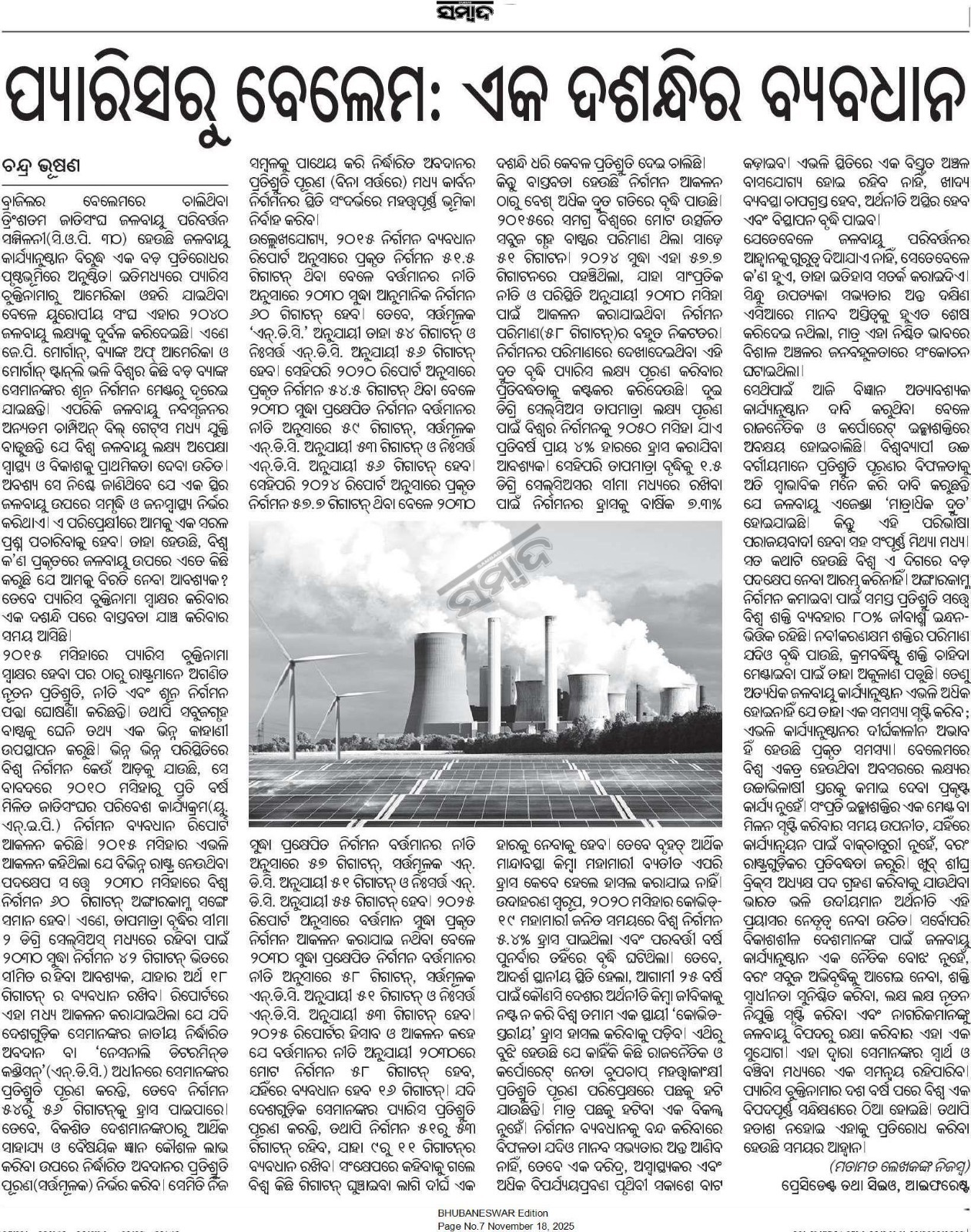

Walk into any ITI classroom in Angul or Jharsuguda and you will see young men and women training for an economy that no longer exists. Many still aspire to permanent jobs in government departments, thermal plants or large factories. Those jobs are quietly shrinking. The new ones are emerging elsewhere — in solar parks, battery plants, EV workshops, waste-processing units and green hydrogen hubs. This is the silent churn in Odisha’s labour market. The state is already attracting large investments in renewable energy, electric mobility, green manufacturing and the circular economy. These projects will create thousands of jobs in the coming years. But will these jobs go to local youth?

To answer that, we must be clear about what green jobs actually mean. These are not just office jobs in climate organisations. They include the technician installing solar plants, the fitter maintaining energy-efficient machinery, the mechanic repairing EVs, the worker handling batteries safely and the small entrepreneur running a waste-reuse unit. These are frontline jobs that reduce pollution, save resources and build resilience, while anchoring local economies.

Our recent study shows that Odisha’s near-term green job pipeline is already sizeable. Between 2023 and 2025, planned green projects generated close to 1 lakh jobs across manufacturing, construction, installation, operations and related services. Green sectors can generate up to 10 lakh jobs by 2030 across 28 value chains, from renewable power and storage to green hydrogen, EVs, batteries, bioenergy and circular economy activities. With a solar target of 7.5 GW by 2030, this is a structural transformation of Odisha’s economy.

At the same time, the state remains anchored in coal, metals and other carbon-intensive industries. Lakhs of families depend on coal mining, thermal power and allied sectors. As cleaner energy expands and automation deepens, many workers will face uncertainty. Districts such as Talcher, Ib Valley, Jharsuguda, Angul and Sundargarh sit at the edge of two futures: one of planned reskilling and new industries, and another of slow job loss, migration and economic decline.

This is Odisha’s double challenge — protecting workers tied to the fossil-fuel economy, while preparing its youth for emerging green and low-carbon jobs. This is what a just transition really means.

Odisha does have a wide skilling network: government and private ITIs, polytechnics and hundreds of training centres. Schemes like Sudakshya have increased women’s participation in technical education, and placement-linked programmes have improved outcomes in some trades. But green skilling remains peripheral.

IFOREST’s survey of 571 students, 30 institutions, 33 employers and 110 workers in the solar and EV sectors reveals a worrying gap. Only 7 per cent students are enrolled in dedicated green courses and nearly half are unaware such courses exist. Employers consistently report that recruits lack hands-on exposure, safety training and familiarity with modern tools.

Between 2023 and 2025 alone, Odisha’s green investment pipeline is expected to generate nearly 98,000 new jobs. Yet under PMKVY 4.0, only 1,778 candidates were trained in green roles across seven districts in 2024–25. This is not a small mismatch. It is a structural breakdown between jobs and skills. In simple terms, the jobs are arriving faster than workers are being prepared.

When green industries cannot find job-ready local workers, they hire from outside. Industrial districts attract investment but not employment. Growth happens, but it passes people by.

So what must Odisha do? First, every large green project must be legally linked to local training. Developers should partner with nearby ITIs, co-train workers before commissioning and certify skills jointly with the state.

Second, the state must urgently build a supervisory and safety workforce. Short, targeted upskilling can convert existing electricians and mechanics into higher-responsibility roles. Third, awareness must start early. Statewide green career-orientation drives across schools, ITIs and polytechnics can reshape aspirations. Finally, Odisha needs a live Green Jobs–Skills Dashboard to track investments, training and placements in real time.

Odisha stands at a decisive moment. Green capital is arriving. If the state moves with speed and intent, this transition can deliver local jobs, revived coal districts and dignified work close to home. If it hesitates, the factories will still come. Only the workers will not.