Air pollution is plaguing the capital and smaller cities across India. But who contributes the most—vehicles, industries, wood-fired cookstoves, or stubble burning? These FAQs address common questions, using latest data.

1. What is the true scale of our pollution crisis?

We are facing a subcontinental-scale problem. The thick haze in Delhi extends across the Indo-Gangetic Plains (IGP). Smaller cities like Bhiwadi, Darbhanga, and Moradabad often report higher pollution levels than Delhi, and rural areas are equally affected.

Pollution levels are 5–10 times higher than national standards and 20–40 times higher than WHO health-based guidelines. Solving this problem requires collective action from every city, state, and sector of the economy to significantly reduce emissions.

2. What are the main sources of pollution in India and Delhi-NCR?

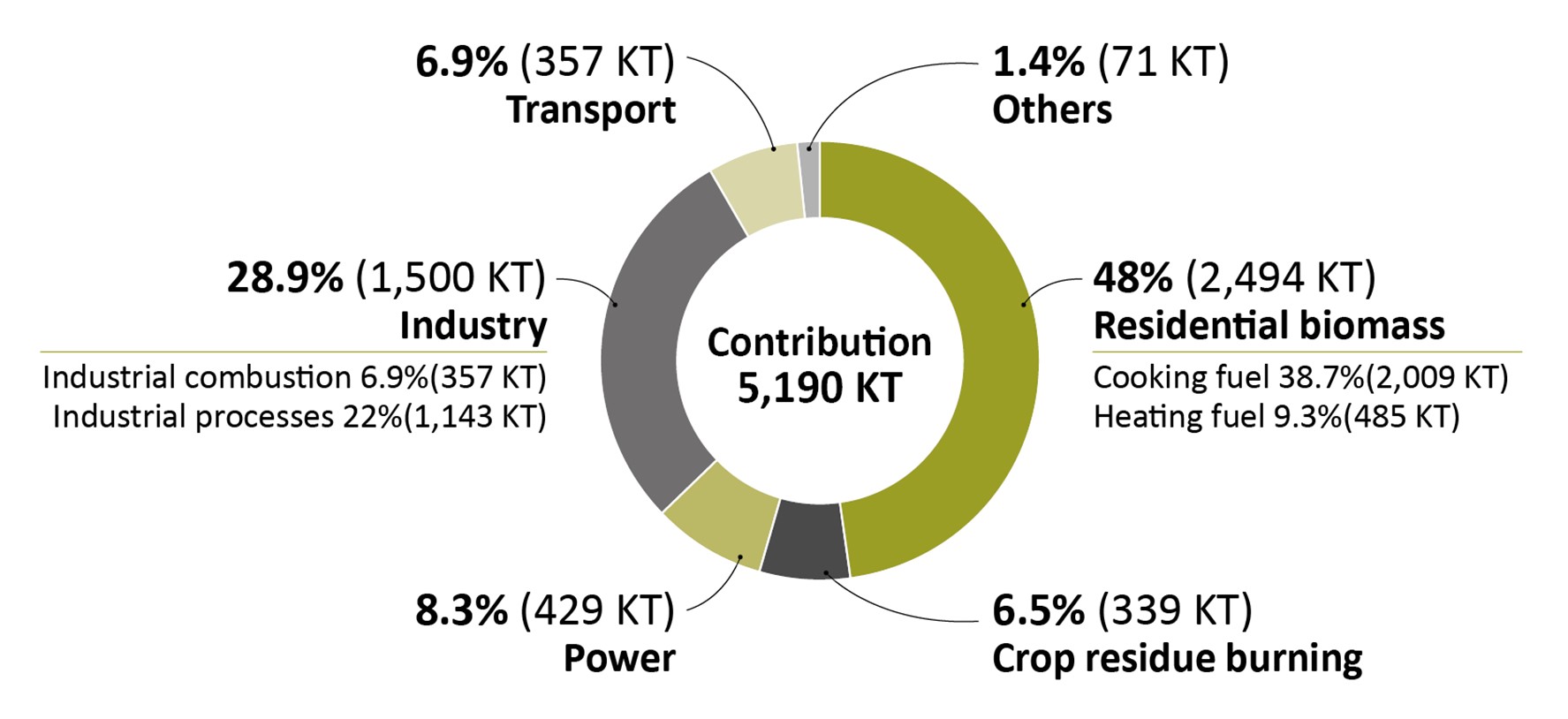

Our research shows that India emits approximately 5.2 million tonnes (MT) of direct PM2.5 annually (excluding natural and manmade dust). Of this:

- 48% comes from biomass (e.g., fuelwood and dung cakes) used for cooking and heating.

- 6.5% comes from open burning of crop residues. Together, biomass burning accounts for 55% of total PM2.5 emissions.

- 37% comes from industry and power plants.

- 7% comes from the transport sector.

Figure 1: PM2.5 inventory of India

Source: iFOREST

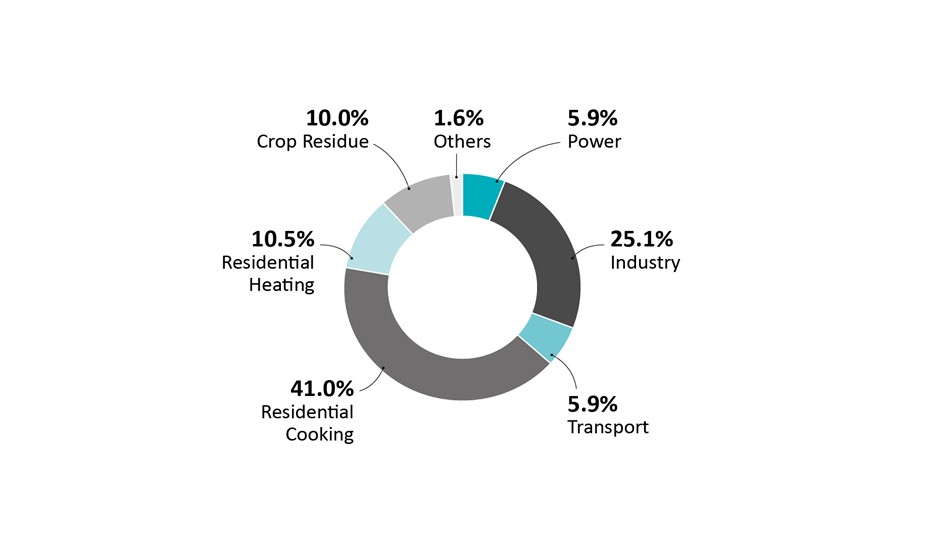

In Delhi-NCR, biomass burning contributes more than 60% of PM2.5, industry accounts for 25%, and transport contributes around 6%.

Figure 2: PM2.5 inventory of Delhi-NCR

Source: iFOREST

3. Are there other studies that support the claim that biomass is a major source of pollution in Delhi-NCR?

Several studies confirm the significant role of biomass burning in Delhi-NCR’s air pollution, including one from the Central Pollution Control Board.

1. Awasthi, A. et al.: Biomass-burning sources control ambient particulate matter, but traffic and industrial sources control volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions and secondary-pollutant formation during extreme pollution events in Delhi, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 10279–10304, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-10279-2024, 2024.

This paper shows that during the smog season, direct PM10 (52 ± 8 %) and PM2.5 (48 ± 12 %) emissions were dominated by different biomass-burning sources.

2. Mishra, S. et al.: Rapid night-time nanoparticle growth in Delhi driven by biomass-burning emissions, Nat. Geosci., 16, 224–230, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-023-01138-x, 2023.

This paper found that biomass burning is the primary cause of intense and frequent night time particle growth during haze development in Delhi.

3. Lalchandani, V. et al.: Effect of Biomass Burning on PM2.5 Composition and Secondary Aerosol Formation During Post-Monsoon and Winter Haze Episodes in Delhi, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 126, e2021JD035232, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD035232, 2021.

This paper too finds that the burning of biomass material is the largest contributor to haze events during post-monsoon and winter haze events.

4. Central Pollution Control Board: Report of the Committee in O.A. No. 19/2021 in the matter of Sanjay Kumar versus State of UP & Ors, in compliance with the order dated 09.09.2021 of the Hon’ble National Green Tribunal, December 2022.

This report of the Central Pollution Control Board, on the direction of the NGT, published the emissions inventory of the entire Indo-Gangetic Plans, found the following:

The total PM2.5 emissions was 2.3 million tonnes. Biomass burning contributed about 35% of the total PM2.5, industries contributed 48.5% and transport sector’s contribution was 5%.

As you can see from the above reports, while numbers can vary dependent on the methodology and scope of the study, there is no doubt that biomass is a major contributor of air pollution in Delhi and in the entire country.

4. Why does biomass burning in homes and fields contribute so much to PM2.5?

The reason is simple: unlike automobiles and industries where some pollution control devices are used, biomass cookstoves and open burning in fields emit all of their pollutants unconstrained into the air. Thus, PM2.5 emission per kilogram of biomass in cookstoves is tens to hundreds of times more than those from per kg of coal in power plants or diesel in automobiles.

An estimate by renowned scientists Kirk R. Smith and Ajay Pillarisetti show that one year of cooking on a traditional chulha emits particles equivalent to the emissions of 20 diesel trucks driving 50,000 km a year and meeting Euro 6 standards. This is precisely why rural areas suffer equally from air pollution. There is ample research evidence to show that outdoor air pollution in India is not just an urban India problem.

5. Are we not blaming and victimising the poor by focussing on biomass?

Absolutely not. The poor, especially poor women and children, are the worst sufferers of air pollution. They are hit twice over. They are affected by indoor air pollution, because of firewood and cow dung cakes burning in their chulhas and they are affected by outdoor air pollution.

We advocate for transitioning the poor to cleaner cooking fuels, reducing their exposure to harmful pollutants. This makes air pollution mitigation a pro-poor and pro-women agenda, as it prioritises vulnerable populations while also addressing the main sources of pollution.

Central Government schemes such as Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY), which enable the poor with cleaner cooking fuels, have been far more transformative in combating air pollution than implementing GRAP, odd even, or other quick fix measures that are implemented each year. We are recommending a new version of PMUY to support the poor households in shifting to cleaner cooking fuel like LPG, biogas or electricity.

6. Are you not equating the luxury emissions of rich to the survival emissions of poor?

When we use the framework of ‘luxury vs. survival’ emissions, which is a construct of the climate change politics between developed and developing countries, we are basically advocating to keep the poor exposed to the worst air pollution. This ‘luxury vs. survival’ emissions politics basically says that let the poor burn biomass and suffer, till the time we can show that we are acting on the rich by focussing on SUVs and large industries. This is what we have done in the last 25 years. Our singular focus has been on automobiles and large industries but it has not made any significant impact on the air quality. ‘Luxury vs. survival’ emissions is one of the most unethical framing of the air pollution issue.

The fact is that the politics over rich vs. poor, farmers vs. city-dwellers, SUVs vs. cook stoves, and Diwali vs. stubble burning have stalled real work on air pollution. We must work on an agenda which helps the poor and small industries to transition to cleaner fuels.

7. What are iFOREST’s key policy recommendations for Delhi-NCR?

- PM Ujjwala 3.0: Our study shows that the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana has been the most impactful air pollution intervention in the last decade. Expanding access to clean cooking fuel across Delhi-NCR could reduce PM2.5 generation by 25%. Achieving this will require a new PM Ujjwala Yojana to transition households to LPG or electricity for cooking. Research indicates a 75% subsidy is necessary to enable exclusive LPG use in low-income households, requiring around Rs. 5,000–6,000 per household annually, similar to the PM Kisan Samman Nidhi. In Delhi-NCR, this initiative would cost around Rs. 6,000–7,000 crore per year, a fraction of the annual healthcare costs associated with air pollution-related diseases. This will be a profoundly pro-poor and pro-women initiative, especially considering that nearly 600,000 Indians, primarily women, die prematurely from indoor air pollution each year.

- Clean Heating Fuel: Across India, over 90% of households rely on biomass and solid fuels to heat their homes during winter, contributing to pollution spikes in December and January. One of China’s pivotal air quality initiatives was a national clean heating fuel policy. While developing a similar long-term plan is essential, in the short term, the Delhi government could ensure that only electricity is used for winter heating and enforce a strict ban on open burning. This approach will yield swift improvements in Delhi’s air quality.

- Package to End Stubble Burning: Stubble burning is a primary contributor to the sharp rise in pollution levels each October and November. Curbing this practice would reduce the occurrence of severe and hazardous air pollution days. Both short- and long-term strategies are needed. In the long term, agriculture in Punjab, Haryana, and parts of UP must transition from intensive rice-wheat farming to a diversified crop system. In the short term, technology and incentives can play a key role. The simplest technological solution is to modify or mandate combine harvesters that cut closer to the ground like manual harvesting, leaving minimal stubble on the ground. Additionally, an incentive of Rs. 1,000 per acre—similar to what the Haryana Government provides—could encourage farmers to manage stubble sustainably, coupled with penalties, such as fine and exclusion from government schemes for those who continue to burn it. This scheme would cost approximately Rs. 2,500 crores annually.

- Energy Transition in Industry: Industry and power plants account for roughly one-third of annual PM2.5 emissions in Delhi-NCR. Reducing these emissions will require both technological upgrades and stricter enforcement. A scheme encouraging MSMEs to adopt cleaner fuel sources, especially electric boilers and furnaces, could significantly curb emissions. For larger industries, stringent pollution norms and enforcement are essential. Shutting down older thermal power plants and enforcing the 2015 standards, which have yet to be fully implemented, will also be critical.

- EVs and Public Transport: Scaling up electric vehicles is crucial for reducing city’s air pollution. Initially, the focus should be on transitioning two- and three-wheelers, as well as buses, since they are already economically viable. Aiming for 100% electrification of new two- and three-wheeler sales by 2030, and converting all new buses to electric by 2025 in Delhi-NCR, would significantly lower vehicle emissions. Additionally, setting a 30–50% electrification target for cars and other vehicles will help accelerate the transition to cleaner urban transport. Apart from EVs, scaling up public transport and NMTs is crucial. This will also need clear city-wide targets and promotion as a lifestyle choice.

- Green Belt Development: Dust pollution from within Delhi and neighboring areas, coupled with seasonal dust from the Thar Desert, has a substantial impact on air quality. Creating a green belt around Delhi would serve as a natural barrier against incoming dust. Additionally, increasing green cover within the city, including roadside and open space greening, is essential to control local dust pollution.

- Strengthen Municipalities: Local sources of pollution—such as dust from roads and construction, open burning, traffic congestion, and inadequate waste management—are best controlled by municipalities. Municipalities must be held accountable for addressing these issues year-round, rather than only during peak pollution seasons. Strengthening the National Clean Air Program to support municipal efforts will be key to achieving sustainable air quality improvements.