The global economy is in recession, and it is predicted to be more destructive than the Great Depression of 1929 and the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007. India too has been hit hard – tens of millions have lost their jobs, and the economy is projected to shrink by 4-9% in 2020-21. The last time the Indian economy contracted by more than 5% was in 1979 when the entire country was devastated by a once in a century drought (and some regions with floods).

Both Morarji Desai’s and Charan Singh’s governments fell, and we had mid-term elections which brought Indira Gandhi back into power. The fallout of this political upheaval was the founding of the Bharatiya Janata Party in early 1980, which successfully challenged the Congress and came to power within two decades. I believe that the India in which we live in today was in many ways created in 1979. The question is: What kind of India will the 2020 economic recession create? And, can we steer the ‘new’ India towards a more just, equitable and sustainable society?

A defining feature of the current economic crisis is the unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus packages being rolled out by the governments to provide relief and revive the economy. According to the International Monetary Fund, the total stimulus package for G20 countries averaged 12.1% of GDP – many times more than GFC. India too has announced a stimulus package worth 10% of GDP (though there are opposing views on this number). A quick analysis of the stimulus packages shows that they are primarily targeted to revive the current economy; hardly any country has thought about the long-term transition.

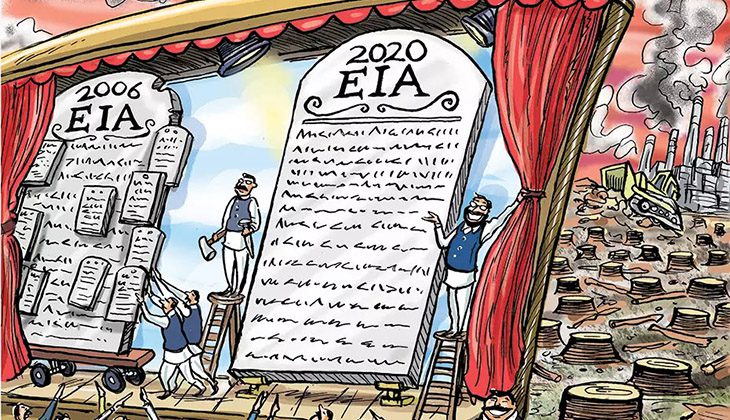

In India too, the focus is on the existing ‘brown economy’ and shovel-ready projects. The attention on the immediate crisis has also relegated climate and environmental concerns to the background. This is evident in the increasing plastic pollution and investments in the fossil fuel industry. Regulatory changes in the environment and labour sectors have also been proposed for the ‘ease of doing business’. While there is nothing wrong in short-term stimulus packages to keep the current economy alive, they must not be environmentally destructive. On the other hand, we also have to ensure that the long-term economic recovery takes into account the social and environmental crisis the world is facing today.

In other words, we must differentiate between a short-term stimulus to jumpstart an economy and a longer-term strategy to transition to a sustainable society. While the former mostly requires fiscal and monetary support, the latter requires long-term investments and serious pricing and policy reforms. The current economic crisis offers us a once in a lifetime opportunity to roll out a long-term strategy along with stimulus packages in core sectors:

- Make agriculture sustainable: Agriculture accounts for 50% land, 85% water, uses a massive amount of chemicals and provides low-income livelihood to 50% of the population. Agriculture is central to building a sustainable society.

- Transform the energy sector: We are at a cusp of change in the energy sector. With stimulus and R&D, we can build a new energy architecture based on renewable electricity, battery storage, smart grids and hydrogen fuel for industries.

- Build resilient infrastructure: Massive amount of money will be spent by the government to build roads, airports, buildings etc as part of the stimulus package. We must make them ‘green’. Instead of roads, we should prioritise railways; instead of concrete jungles, we must build sustainable cities.

- Invest in nature: Reversing deforestation and desertification and enhancing soil, wetlands and forests will build resilience against climate change and also provide massive livelihood opportunities.

- Support local and small businesses: For jobs, sustainability and resilience of the supply chain, local small businesses are going to be the key. Government policies must support the development of efficient and green small businesses.

- Invest in social capital and governance: None of the above would be possible without an educated and healthy society and good governance.

If we consider the experience of the past, then the economic recovery is going to be a long haul. The New Deal enacted by Franklin Roosevelt to respond to the Great Depression lasted for seven years (1933-39). Rebuilding in India will also need time and money. We must spend these rethinking about the type of economy and social system we need and want in the future.